Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

A root canal is a common dental treatment for a tooth with inflamed or infected pulp, usually due to a deep cavity or trauma to the tooth.

Few dental treatments inspire fear like the root canal. But unlike what you might see in the movies, root canal treatment is associated with very little pain.

On the other hand, root canals do carry some risks. They are often prescribed when another treatment is more appropriate or should be preferred. Biological dentists, in particular, generally avoid this procedure and recommend alternatives.

Below, we discuss exactly what a root canal is, how to know if it’s right for you, what to expect, and other common questions.

IF YOU PURCHASE A PRODUCT USING A LINK BELOW, WE MAY RECEIVE A SMALL COMMISSION AT NO ADDITIONAL COST TO YOU. READ OUR AD POLICY HERE.

What is a root canal?

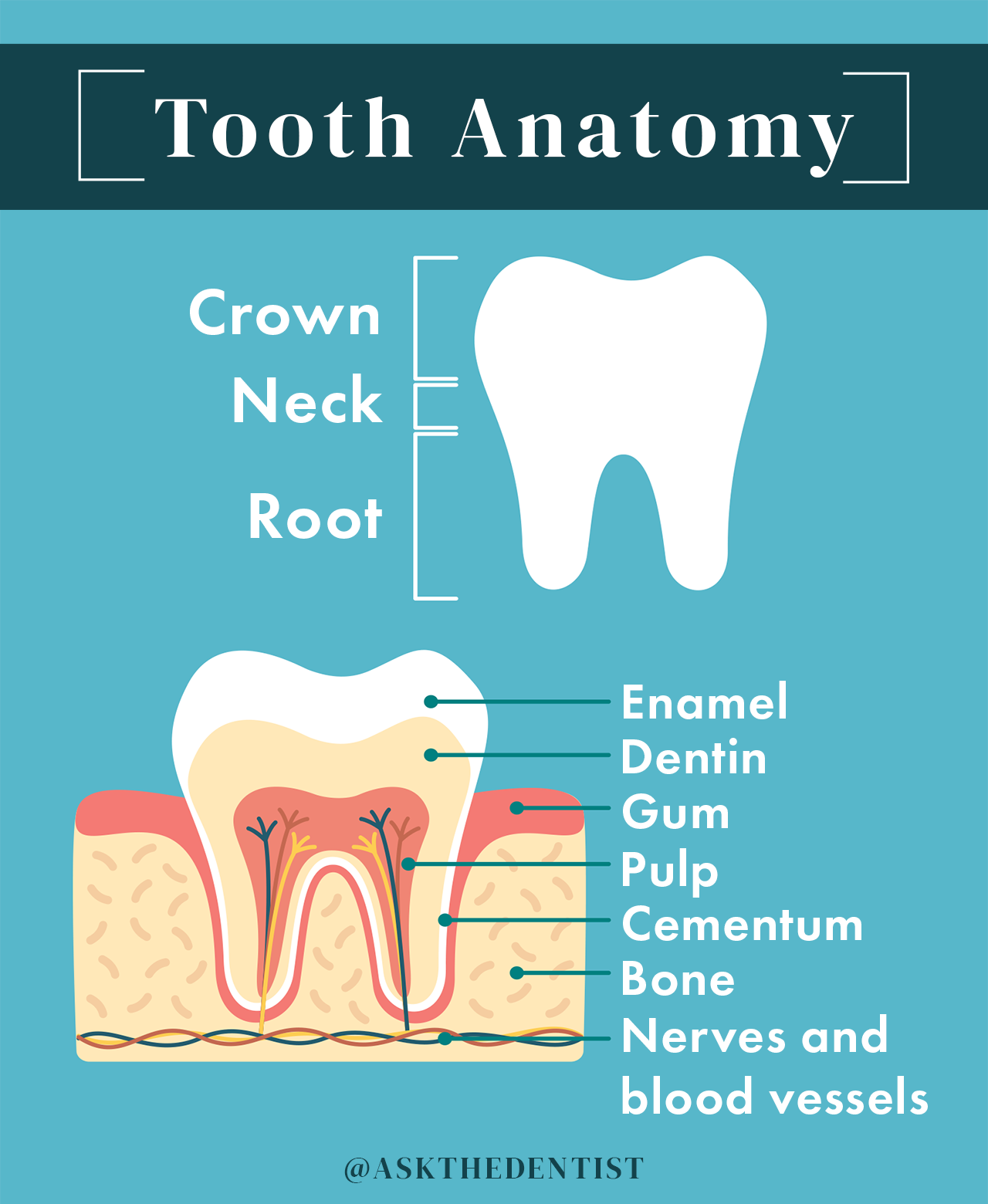

Root canal therapy is a type of dental procedure used to preserve a tooth after the pulp of the tooth has become inflamed or infected. This is typically caused by a deep cavity or physical trauma to the face or teeth.

Dental pulp is the soft tissue found inside the tooth containing connective tissue, nerves, and blood vessels.

During a root canal, a dentist or endodontist will clean out the infected tissue from your pulp chamber, then disinfect, fill, and seal the tooth. In most cases, a crown will be placed on top of the tooth structure to prevent cracking or chipping.

A root canal procedure allows your dentist to preserve (not save) an infected tooth by removing infected tissue and sealing it.

Root canal procedures may also be referred to as:

- Root canals

- Endodontic treatment

- Root canal therapy

- Root canal treatment

Root canals are an appropriate treatment for a tooth with irreversible pulpitis.

Pulpitis, or inflammation of the tooth pulp, can be reversible or irreversible. Once the nerve tissue has died as the pulp’s infection has spread, irreversible pulpitis results.

At that point, a tooth cannot be saved as a living structure.

A root canal procedure can “preserve” a tooth, but not “save” it.

By the time you need a root canal, it’s too late to save the life of the tooth because it’s already infected and dying.

Some people refer to this as “mummifying” a dead tooth.

Preserving tooth structure benefits your oral health because it won’t affect orthodontic growth or your bite. If your dentist extracts a diseased tooth without filling its space with an implant, your teeth may shift and cause orthodontic problems.

The most common risk of root canal treatment is tooth fracture. The inside of the tooth has been scraped out, leaving the outer shell of the tooth dry, brittle, and prone to breakage.

That’s why a root canal procedure almost always requires a second procedure shortly afterward: a dental crown. A root canaled tooth needs the protection of a crown because you’ve carved out the tissue inside it.

A dental crown is a rigid covering, formed to look like a natural tooth, that is stronger than enamel. It preserves the structural integrity of the tooth and reduces the risk that it will break as it weakens over time.

Get Dr. B’s Dental Health Tips

Free weekly dental health advice in your inbox, plus 10 Insider Secrets to Dental Care as a free download when you sign up

How do you know if you need a root canal?

What causes the need for root canal treatment? Irreversible pulpitis (infection and inflammation of dental pulp) is what caused the need for a root canal or similar treatment option. This is usually caused by a deep cavity or injury/trauma to the tooth.

Irreversible pulpitis cannot be healed or reversed by any natural or conventional means.

In the case of tooth decay, you may be able to catch pulpitis before it becomes irreversible. To increase your chances of catching it early, practice good dental care, don’t skip dental checkups, and talk to your dentist anytime you develop a toothache.

Signs you need a root canal may include:

- Tooth pain: Pulpitis will cause pain that may be persistent or come and go. It may be worse when you eat or bite down. Lingering pain, or pain caused by hot or cold stimuli that remains for several minutes or hours, is a telltale sign of irreversible pulpitis and the need for a root canal. Positional pain that occurs when you stand up, lay down, or run in place, may indicate a tooth abscess and a root canal. Spontaneous pain that happens without warning may also indicate an inflamed pulp. It’s possible for pulpitis to cause referred tooth pain that manifests in other teeth or your ear, face, or jaw.

- Bump on the gum (fistula): A fistula is a small white, yellow, or red pimple-like bump that appears on the gum. This tells your dentist that there is an infection because pus, blood, and infectious materials are trying to get out and the body is trying to “vent” them. The problem is that a fistula can mislead a dentist as to which tooth needs a root canal — it doesn’t always appear next to the infected tooth.

- Swollen gums: As an infected tooth tries to “vent” the toxic results of infection, it may also cause gums to swell, redden, and become tender.

- Color change of the tooth or gums: A dead or dying tooth may turn grayish over time as its blood supply diminishes. This is more likely to be noticeable on a front tooth than a back one. The infection can also darken the gums around the tooth.

- Loosening tooth: As infection spreads, it may soften or degrade the bone in which the tooth sits. This can cause your tooth to become more mobile, wiggling upon contact.

- Cracked tooth: If your tooth has a crack that extends down into the tooth root, it is usually impossible to save the tooth and it must be treated with a root canal or an alternative treatment option.

- Deep cavity: A cavity can cause many of the signs above, such as pain. Your dentist may use x-rays or a cone-beam CT (CBCT) to diagnose the extent of your tooth decay.

- Tooth abscess: Also known as a periapical abscess, this pus-filled infectious area beneath the tooth root occurs as a result of irreversible pulpitis, often due to an untreated cavity. This is not the same thing as a periodontal (gum) abscess, which may not suggest the need for a root canal.

- Dark blood from the pulp: When your dentist opens your toot for a root canal, he or she may be able to identify irreversible pulpitis from visibly darker blood than usual.

- Red-yellow pus: Not all inflamed teeth bleed. Often, a sure sign of irreversible pulpitis upon opening the tooth is oozing, reddish-yellow pus.

Diagnosing a root canal is a complex process that differs between dentists. There is no cut-and-dry way to diagnose a root canal. This process is part science, part art form, to discover the degree of infection within a tooth.

Do you need a root canal if there’s no pain?

If your dentist identifies irreversible pulpitis, you will need a root canal regardless of whether or not pain is present.

Your tooth nerve may die, temporarily relieving pain. Your dentist may put you on antibiotics that shrink the infection, which would also cause pain to subside.

However, irreversible pulpitis must be treated by root canal or extraction. Otherwise, it can cause serious systemic health issues.

What to Ask Before Agreeing to Treatment

In my practice, I’ve met many patients who were prescribed root canal therapy because a practitioner was in a hurry or looking for the “simplest” option, rather than the best option.

For instance, a dentist may suggest a root canal for a large cavity even if the pulp is not irreversibly inflamed and a filling would suffice.

Dental insurance covers it, the general dentist doesn’t have to place a filling that requires more-than-average finesse, and — I hate to say it, but it’s true — the price tag is higher.

I highly recommend asking your dentist the following questions before you say yes to a root canal to prevent unnecessary dental work:

- Is a root canal absolutely necessary?

- Is it possible the tooth will recover and not need the root canal?

- How did you come to the conclusion that I have irreversible pulpitis?

- Why did the pulp die?

- What if I don’t do the root canal?

- Should I skip the root canal and go right to the extraction and implant?

- Will my infection spread to other teeth or to my bone?

- How confident are you that a root canal will be successful?

- Should I have this done by a specialist or can you do as good of a job as a specialist can?

In general, many root canal symptoms can often be attributed to causes other than irreversible pulpitis. Until your dentist or endodontist is fairly certain that irreversible pulpitis is to blame, root canal treatment should not be prescribed.

What to Expect During a Root Canal Procedure

A root canal procedure can be done in 1 or 2 visits. For retreatments (in which a tooth has already received endodontic treatment), 3 visits may be requested. Each visit should take 90 minutes or less.

How long does a root canal take? A root canal procedure takes 30-90 minutes per visit. For simple cases of teeth with one root, each visit will probably 60 minutes or less. Complex cases take closer to 90 minutes per visit.

Why do root canals take 2 visits? Depending on the provider’s preference, root canal treatment may be done in 2 or more visits for more thorough cleaning. The number of visits for root canal therapy has no significant impact on pain levels or treatment success rates.

Should your root canal be done by your dentist or a specialist? Specialists in root canal therapy are called endodontists. An endodontist should perform your root canal procedure if you have complex canals or if your general dentist refers out root canal cases. However, all dentists are trained to perform root canals during dental school.

Before the Procedure

Before your root canal procedure, your dentist will probably take x-rays or a cone-beam CT (CBCT) and perform a physical exam to identify irreversible pulpitis.

Your dentist may prescribe antibiotics before the procedure if:

- You are immune-compromised

- You have an existing tooth abscess

- You present with a fever

- Your infection had a rapid onset

- You have developed a system-wide infection

During the Procedure

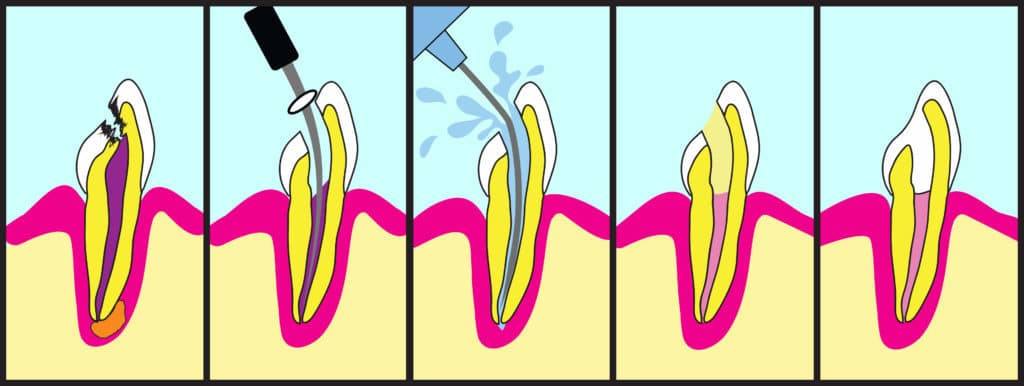

This is how a root canal procedure is performed, step-by-step:

- X-rays and exam: The dentist or endodontist will take a new set of x-rays and perform another physical exam. Many x-rays will be taken to make sure that the instruments are in the correct location to remove the infected tissue.

- Numbing: You will receive full local anesthesia to numb the tooth and surrounding area. This local anesthetic is more than what’s required for a filling because your dentist must remove the nerve. Your dentist will typically not put you under sedation (to sleep) for a root canal, but you can request sedation if you’re anxious.

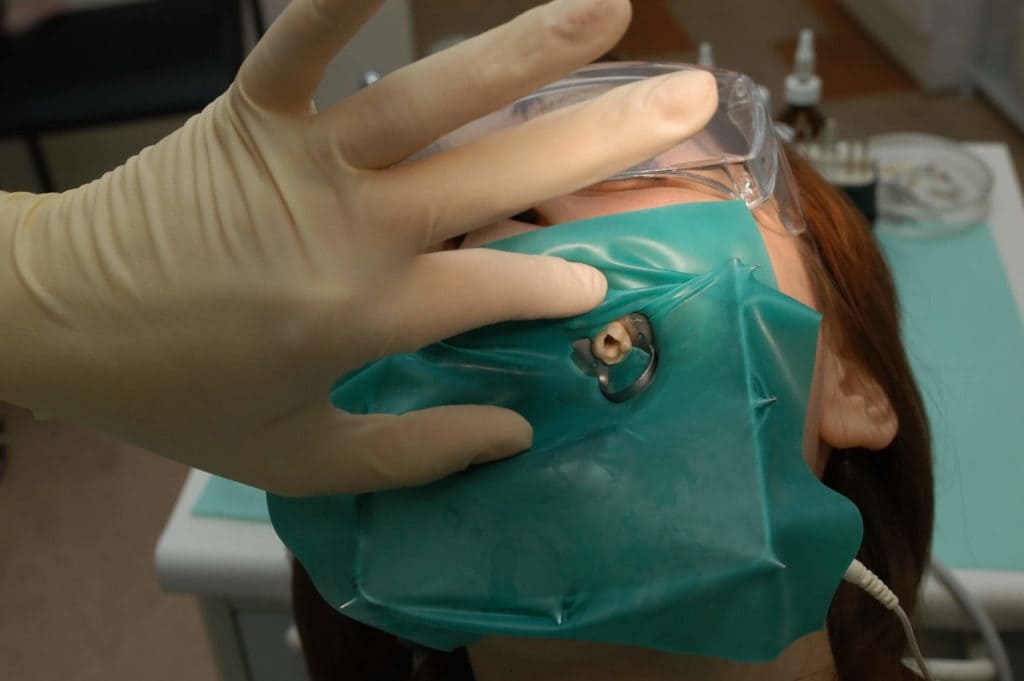

- Rubber dam: A sheet of latex, called a rubber dam, will be placed over your mouth. This prevents bacteria from the rest of your mouth from entering the tooth. The dental dam also stops medications inside the tooth from being swallowed.

- Opening: An opening will be drilled into the top of your tooth.

- Cleaning and shaping: Using very refined drills and files, your dentist will remove the inflamed or infected pulp, carefully cleaning out and shaping the inside of the tooth.

- Irrigation: The main pulp chambers will be irrigated with water and, in most cases, an antibacterial agent to eliminate any remaining bacteria. These chambers must be fully dry before moving on to the next step.

- Filling: Next, the dentist will fill and seal the tooth so it’s closed off to infection. The tooth is filled with gutta-percha, a biocompatible filling material, combined with rubber cement. A temporary filling will be placed until you get a permanent crown.

In some cases, posts will be inserted inside the tooth during the filling process. I do not recommend posts to patients, as they have a tendency to crack the teeth.

Do root canals hurt? Root canals do not hurt at all during the procedure. If the dentist is skilled at delivering the local anesthesia, you won’t feel a thing. There may be minor pain and soreness as you recover.

Sometimes, a dentist will begin the root canal and things go wrong — this can be a good thing!

If your dentist gets inside the tooth and is presented with new information that changes the chances of success of a root canal, he will stop to tell you. This gives you the choice to abort the procedure before proceeding with a root canal with lower chances of success than you both originally thought.

Reasons to stop a root canal include:

- Separated instrument: An instrument breaks off inside the tooth.

- Calcified root canal: If the root canal is calcified, your dentist won’t be able to negotiate it well. In these cases, endodontic surgery like an apicoectomy may be required.

- Fracture: Once the tooth is opened, your dentist might see a fracture not visible on the x-ray. Seepage can occur at the fracture line, which can lead to bone loss. If you lose bone around the tooth, you lose the support of the tooth. In these cases, an extraction with a dental implant will offer a much better prognosis.

- Curved root: Also called “complex canal morphology,” this kind of tooth root is hard to navigate. Complex root canal anatomy — lots of hard-to-navigate twists and turns — reduce the potential success rate.

Your dentist should only do the root canal if conditions are ideal.

You can still drive home if you’ve been given only local anesthesia.

Getting a Crown or Filling

After your root canal treatment is complete, you’ll need to go back to your dentist for a crown or a filling. Crowns or fillings should be placed within 1-4 weeks after a root canal.

Do you need a crown after a root canal? If you have a root canal done on a molar or pre-molar (your back chewing teeth), you need a crown after root canal treatment. Most incisors and canines (front teeth) do not require a crown.

Some people wait to get a crown so that they don’t max out their insurance, but this can be a dangerous risk. If the tooth fractures before a crown is placed, you lose the investment of the root canal entirely.

In some cases, your dentist will recommend only a filling to protect the tooth.

Crowns benefit teeth in the following ways:

- Better success rate: Your root canal treatment is more likely to last without repeated treatment if a crown is placed on a molar or premolar. Root canal without crown is 6 times more likely to fail, according to one study over an 11-year period. Another study found that a root canaled tooth without a crown has a 63% chance of failure within 5 years.

- Reduced chance of fracture: Without a dental crown, your tooth may become more susceptible to fracture over time. This is because the “mummified” tooth will become brittle as it no longer receives blood flow.

- Natural-looking tooth: You can get a crown to match the color of your remaining teeth to hide discoloration and appear just like a natural tooth.

- Lower risk of infection: A crown covers the inside of the treated tooth to prevent most bacteria from getting in, which could otherwise cause a new infection and require retreatment.

The procedure for placing a crown is done in these steps:

- The tooth is filed down to remove the outer layer.

- Impressions are taken of the new tooth shape. For in-office crowns, your dentist will take an optical impression.

- The impressions are sent to a lab or used to create a crown in-office.

- If your dentist doesn’t have the equipment to make a same-day crown, a temporary crown will be placed and you’ll wait several days while the crown is being manufactured.

- The crown is placed on your tooth and secured by mechanical retention. Dental cement is used to prevent saliva or any other substance from getting under the crown.

Antibiotics & Root Canal Therapy

Antibiotics have been part of the standard of care for root canals for many decades. However, more recent research shows they are frequently unneeded and may contribute to antibiotic resistance.

Dentists frequently prescribe antibiotics before and after endodontic treatment for reduced chance of systemic infection, reduced pain, increased success rates, and a variety of other reasons.

The problem is that antibiotics actually have no significant impact on root canal outcomes in almost any case.

One review of antibiotic use for root canals found that dentists are most likely to prescribe antibiotics for root canals due to the placebo effect and a lack of education, not a clinical need.

A 2016 review by the American Dental Association (ADA) found that the only legitimate reasons for antibiotics before or after a root canal were a present systemic infection, fever, or both.

The European Society of Endodontology holds the position that antibiotics should be prescribed only in the following cases:

- Systemic infection caused by a tooth abscess

- Tooth abscess in an immune-compromised patient

- Rapid onset infection with outward symptoms in 24 hours or fewer

- Replantation of a tooth that has been knocked out (avulsed) due to trauma

- Trauma to the soft tissue of the mouth that requires treatment

How long can I go before getting a root canal?

Once your dentist has diagnosed irreversible pulpitis, you need to get a root canal (or alternative treatment) right away. Your provider may prescribe antibiotics before treatment, in which case you may need to wait to finish your round of antibiotics.

When you find out you need a root canal for irreversible pulpitis, it’s like a ticking time bomb because the infection will eventually get out of control.

Pressure, swelling, and pain are likely to get worse. You might develop a bad taste in your mouth or experience numbness. The infection could spread to more vulnerable tissues, like your heart.

Yes, a tooth infection can kill you.

In the 1600s, tooth infections made the list of the top 6 causes of death in England. As recently as 1908, tooth infections had a mortality rate of up to 40%. That’s worse than smallpox!

Complications of infections like these, such as those from a tooth abscess, are extremely dangerous. Don’t wait for treatment!

Root Canal Recovery

For fast root canal recovery:

- Don’t smoke for at least 7 days after the procedure

- Avoid chewing hard, crunchy, very hot, or very spicy foods/drinks or any foods with a sharp edge (like sourdough bread) for 1-2 days

- Avoid drinking alcohol for 1-2 days, as this may increase bleeding

- Don’t bite or chew on the treated tooth until a permanent crown has been placed

- Brush, floss, and maintain good oral hygiene as normal

Can you drive after a root canal? You should be able to drive immediately after a root canal procedure unless sedation was used. Root canals usually involve local anesthetic, but sedation may be requested for patients who are anxious about the procedure.

You should have a follow-up exam 6 months after your root canal. After that first follow-up, your dentist should closely examine (and, preferably, do a CBCT on) your treated tooth every 3-5 years to check for a failed root canal and reinfection.

Pain After a Root Canal

It’s common to have a little soreness after your procedure, but extreme pain after a root canal is abnormal. One study estimates that long-term pain happens after only 12% of root canal treatments.

If you do have pain, it usually peaks 17-24 hours after the procedure. To avoid this, keep your head elevated with a wedge pillow while sleeping for the first 1-2 nights.

Soreness from keeping your mouth open for a long period of time should go away after 1-2 days. However, if you have persistent TMJ pain, this soreness and stiffness may remain for 6-8 weeks, particularly if a dental dam was used.

You may have pain in the gum or other soft tissue around the root-canaled tooth from inflammation or damage during your root canal treatment. This should clear up within a week or two.

You can use over-the-counter pain medications like ibuprofen (Motrin) or acetaminophen (Tylenol) to relieve any pain for the day or two after a procedure.

Persistent pain (3 months or more) after root canal usually happens when you bite down or palpate the treated tooth. It’s frequently associated with:

- A filling that is too high

- A severe infection before your root canal

- Previous painful dental work

- Existing chronic pain issues

More women than men tend to develop long-term root canal pain.

If you experience severe or sudden pain in the tooth weeks, months, or years after your root canal, it may be a sign of root canal failure. Contact your dentist immediately.

Root Canal Cost

Before dental insurance, a root canal procedure in the United States costs anywhere from $500-$2,250. A crown after root canal ranges from $600-$2,500, depending on the material.

When performed by a general dentist, a root canal for a front tooth will cost between $500-$1,000. Molars (back teeth) cost between $1,000-$1,500 with a general dentist. Endodontists (root canal specialists) usually charge about 50% more for a root canal procedure.

A high-quality cubic zirconia (new porcelain) crown costs around $1,300, while a gold crown — which lasts longer than any other material — runs about $2,500.

Your total cost may be as little as $1,100 and as much as $4,750 for a single root canal and crown.

The cost of your treatment will also differ depending on where you live. In general, a higher cost of living will mean a higher cost for dental treatment.

How much are root canals with insurance? Root canals are almost always covered by dental insurance but the rate of coverage differs by plan. In addition, your coverage probably applies only after you’ve met your yearly deductible.

Many traditional plans cover root canals at 80% and crowns at 50% of the billed cost. However, check your insurance plan and talk to your insurance company before treatment to be sure.

And remember: Most dental plans cap yearly coverage amounts at $1,500 or less. You may be responsible for a higher percentage of the cost than you initially expect if your dental plan reaches its cap.

Are root canals worth the cost? Root canals are often worth the cost because they have a high success rate and cost less than high-quality alternatives. The price tag for extraction with a dental implant, for instance, is significantly higher than a root canal and crown (potentially 2-3 times more).

Complications of Root Canal Therapy

Potential complications of a root canal (not including those related to anesthesia) include:

- Reinfection: A cyst or bone infection can occur years after root canal treatment, most often from a badly done procedure. Underfilling and/or not properly disinfecting the canals, as well as the presence of a broken instrument, make this outcome more likely.

- Partial root filling: It’s possible for a dentist not to completely fill the tooth root(s) during a root canal procedure, particularly if you have a complex canal structure. This may require retreatment and should be done by an endodontist.

- Canal or tooth crown perforation: If a dentist perforates (creates a hole) in the root canals or in the crown of your tooth, you’ll probably need to have the tooth extracted.

- Instrument breakage: During 2.7-3.7% of root canals, an instrument breaks during treatment. Your dental provider should inform you if this occurs and let you choose whether or not to have them remove the broken piece. Even if the piece remains, this may or may not impact the success of your root canal treatment.

- Overfilling the canal: If the canals were overfilled and the tooth is near the sinus cavity or nerve canal, this may cause post-operative pain. The pain may subside without further treatment. However, the excess filling material may need to be removed if it causes bone inflammation or significant pain, or is near the mandibular nerve or maxillary sinus.

- Discoloration: Darkening tooth color is usually a sign of blood or a poorly done root canal. This complication can often be avoided by the use of a rubber dam, magnification device, and clean instruments.

- Sinus drainage: It’s possible to have drainage and sinus pain after a root canal. You may notice it tastes or smells like the antibacterial solution used to disinfect your tooth during the procedure. Most likely, this occurs if the space left behind after a large abscess allowed passage of the solution into your sinus cavity. This is probably not dangerous and should go away after a short period of time. However, if you experience sudden, severe pain or any facial swelling, contact your dentist right away.

The main concern of root canal therapy is that they are never 100% clean, meaning there is always bacteria left behind in the auxiliary canals off the main root canals.

This is true for every single root canal procedure, but the quality of treatment has a major impact on this. As a study in the Journal of the American Dental Association puts it:

“Endodontic procedural errors are not the direct cause of treatment failure; rather, the presence of pathogens in the incompletely treated or untreated root canal system is the primary cause of periradicular pathosis.”

In other words, a badly done root canal is far more likely to fail and cause problems in the future.

I recommend all patients get a cone-beam CT (CBCT) every 3-5 years after root canal therapy to properly check for lesions or other signs of root canal failure. CBCT is a far more reliable method to recognize failure than a traditional x-ray.

Lesions and reinfection can occur with or without pain, so don’t rely on symptoms to determine whether or not your root canal was successful.

Prognosis & Long-Term Outlook

Root canal success rate and long-term prognosis are remarkably high, particularly when a crown is placed on the treated tooth.

The overall success rate for root canal procedures is between 80.1%-86%.

The success rate decreases most significantly (below 90%) after 5 years have passed.

A patented same-day root canal treatment known as the GentleWave System boasts a success rate of 97.3% after 12 months. This is similar to the treatment outcomes of traditional root canal therapy. However, the GentleWave system does result in significantly fewer reports of postoperative pain than traditional root canals.

Factors that reduce the chance of root canal success include:

- Treatment by a general dentist, rather than an endodontist

- Necrotic pulp (dead tooth pulp) and/or irreversible pulpitis

- Periodontal (gum) disease

- Poor procedural technique (including underfilling, overfilling, or instrument breakage)

- Fracture to the treated tooth and/or crown

- New bacterial infection

- Male gender

- Hispanic/Latinx ethnicity

How long does a root canal last? On average, root canals last 10 years or more. Some root canals last a lifetime.

Are root canals safe?

Root canals are safe for most people but may cause problems over time. To watch for root canal failure, get a cone-beam CT (CBCT) every 3-5 years after endodontic treatment to check for failure.

Major organizations, like the American Dental Association (ADA) and American Association of Endodontists (AAE), speak highly of the benefits of root canals. According to both the ADA and AAE, root canals pose no major danger whatsoever.

Other groups, including the International Association of Biological Dental Medicine (IABDM), do not recommend root canal therapy.

The Root Cause documentary and some alternative dental practitioners present root canals as extremely dangerous. Their theories often cite root canal treatment as a hidden cause of any number of systemic, chronic diseases.

To date, no published, peer-reviewed scientific evidence supports the majority of these hypotheses.

However, if you are at a high risk of root canal failure due to compromised immunity or other factors, you may want to opt for an alternative treatment.

Pros & Cons of Root Canal Treatment

Is a root canal right for you? If your dentist has identified irreversible pulpitis, a root canal is one of only a few options for treatment.

Many dentists will recommend root canal for cases of reversible pulpitis for a number of reasons. In these situations, I would ask about getting a large filling instead.

Consider the pros and cons before deciding if a root canal is the best option for your case.

Root Canal Pros:

- You don’t have to extract the tooth.

- You don’t lose the bone around the tooth.

- Your orthodontic growth, bite, and normal tooth use will remain the same.

- You will no longer experience hot or cold sensitivity in the treated tooth.

- The recovery pain and recovery time are mild and brief.

- The rate of success is very high even after 10 years (over 80%).

- It’s less expensive than extraction with an implant.

Root Canal Cons:

- There’s no such thing as a 100% clean root canal — some bacteria will always be left behind.

- If your root canal fails, you’ll need retreatment of some kind, which carries a significant additional cost.

- There are anecdotal reports that root canals are associated with systemic disease months to years after treatment. If you’re a healthy person, this is likely not an issue. But if you’re on the edge of optimal health, it’s possible your body can’t handle it. If you’re immunosuppressed or in poor health, you may want to consider other options.

- It can be hard to sit with your mouth open for a few hours during the procedure, particularly if you struggle with TMJ pain.

If possible, ask a trusted friend or family member to help with your decision if you’re already in significant pain. “Deciding under the influence,” as I call it, can lead to hasty decisions — especially if your tooth hurts a great deal.

Root Canal Prevention

Preventing the need for root canal therapy involves reducing your risk of untreated tooth decay and trauma to your teeth.

To reduce your risk of tooth decay:

- Practice good oral hygiene (flossing, brushing, oil pulling, etc.)

- Use a remineralizing toothpaste like Boka or RiseWell

- Eat foods that prevent cavities

- Limit your intake of sugary, acidic, and highly processed foods

- Avoid antibacterial oral care products like regular mouthwash, which disrupt your oral microbiome

- Prevent dry mouth by mouth taping and practicing nose breathing

- See your dentist for a cleaning and exam every 6 months

To prevent tooth decay from progressing to the point of a root canal:

- Never ignore a toothache — always discuss new tooth pain with your dentist

- Don’t put off dental work for tooth decay unless you’re actively reversing cavities

- Consider regenerative endodontics, a stem cell endodontic therapy, if you have existing pulpitis

To reduce your risk of trauma to teeth:

- Always wear a mouthguard when playing sports or during athletic activity

- Use your teeth only for eating — no opening packages, chewing on pencils, etc.

- Be cautious in situations where falling is likely

- Practice safe driving — always wear a seatbelt

Root Canal Alternatives

There are risks to root canal therapy, which is one reason why many functional dentists may not frequently prescribe this dental treatment.

Depending on what kind of specialist you talk to, their recommendation for treatment may be different. Oral surgeons often prescribe an extraction with an implant, while an endodontist is more likely to recommend a root canal.

Depending on your case, there are 3 possible alternatives to root canal treatment:

- Dental fillings

- Extraction with dental restoration (implant, bridge, or dentures)

- Regenerative endodontics

Root Canal vs. Fillings

For cavities that have not caused irreversible pulpitis, a large filling may be a better option than a root canal. A filling allows you to retain a living tooth, which will be more resistant to new cavities and fracture than an endodontically treated tooth.

Fillings are not an option once the tooth pulp has become irreversibly inflamed or died.

Why would a dentist recommend a root canal instead of a filling for a tooth with reversible pulpitis? Each practitioner has preferences for treatment protocols. Many dentists turn to root canal when a filling could work for a few basic reasons:

- Large fillings require great technique. Some providers aren’t confident in their ability to successfully complete this treatment, particularly if the top of the tooth must be made very thin to place the filling. This could potentially lead to the need for follow-up dental work.

- Irreversible pulpitis is difficult to diagnose. As explained, determining if a patient has reversible or irreversible pulpitis is not always straightforward. If a dentist is unsure, he or she may opt for the treatment most likely to be successful in either case — a root canal.

- Root canals cost more. The vast majority of dentists I know are excellent providers who care about their patients. However, a dental practice is a business, and it’s more profitable to bill for a root canal than a filling. Root canals are almost always covered by dental insurance, so there’s little chance that the insurance company will refuse to pay.

If you’re not confident in the prescription of a root canal and believe a filling would be better, consider getting a second opinion to be sure.

Root Canal vs. Extraction

Tooth extraction followed by a restorative procedure is the only alternative option besides a root canal for irreversible pulpitis.

Restorations that can be done after an extraction include:

- Dental implant

- Dental bridge

- Dentures

A dental implant is the preferred option if you decide against a root canal, as it is less likely to lead to bone loss or gum problems than dentures. It’s a highly effective procedure and the implant allows for natural chewing and aesthetics.

Both a root canal and extraction with a dental implant have the same probability of long-term success. Dentists make treatment decisions in these cases based on factors like cost-benefit ratio, patient preference, systemic health issues, and the probability of root canal success.

After extraction of multiple side-by-side teeth, your dentist may suggest a bridge connected by implants on either side.

If you are missing a large number of teeth and are on a limited budget, you may opt for dentures instead of multiple dental implants and/or a bridge.

Root Canal vs. Regenerative Endodontics

Regenerative endodontics is a relatively new method of endodontic treatment to restore inflamed dental pulp.

First introduced in 2004, this practice involves irrigating and disinfecting root canals of a tooth with pulpitis but not removing the infected pulp. Then, the tooth is agitated to cause bleeding at the apex of the tooth roots.

This bleeding provides the inflamed pulp of the tooth with a large number of mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs) that may heal the root of the tooth. Other stem cells may be manually injected into the tooth root.

Regenerative endodontic therapy may be successful in 91% of cases at reversing pulpal inflammation. In some cases, treatment is effective even when the pulp has initially been diagnosed with irreversible pulpitis.

This may not be the best option for many people because:

- The field of regenerative endodontics is relatively new and untested

- The procedure itself requires an extensive amount of perfected technique

- It may not be easy to find a provider near you

- This procedure is less likely to be covered by dental insurance

- As a more experimental procedure, regenerative endodontics may be prohibitively expensive

However, this could be the future of what we currently know as root canal therapy.

Click here to browse clinical trials for regenerative endodontics.

FAQ

What root canal irrigants are used to clear the pulp chambers and kill bacteria before the tooth is filled?

Root canal irrigants include:

- Ozone

- Sodium hypochlorite (NaClO)

- Chlorhexidine

- Calcium hydroxide [Ca(OH)2]

Integrative endodontic treatment is partial to ozone treatment. More than any other bactericidal solution, ozone may effectively eliminate a significant amount of bacteria in the small canals off the main pulp chamber.

There is also no risk of antibiotic resistance with ozone, unlike other alternatives, which could lead to stronger bacterial strains. Ozone may also be used on its own or with other antimicrobial agents.

More recently, the use of antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) has been studied as an adjunct (add-on) to these agents. aPDT can result in a significant reduction of bacteria within the pulp chamber.

What are my options for root canal sedation?

Root canal therapy does not require sedation. However, if you want or need to be sedated for a root canal due to dental anxiety, there are 3 options:

- Minimal sedation: Your dentist can use nitrous oxide to ease your fear. You may also be given a mild oral sedative about an hour before your procedure. You’ll be awake during treatment but mostly unconcerned with the sounds or sensations. The effects will wear off shortly after the procedure and you should still be able to drive home.

- Moderate sedation: Formerly dubbed “conscious sedation”, this kind of sedation can be achieved with higher doses of an oral sedative like Valium or through an IV. You may be groggy enough to sleep during the procedure but will be easy to wake up.

- Deep sedation/general anesthesia: Deep sedation puts you completely “to sleep” and you can’t be easily awakened. You will probably have no memory of the procedure or the period of time shortly after you wake up. This level of sedation requires an additional two-year certification for a dentist or the use of an in-house anesthesiologist. You’ll need someone to drive you home after undergoing deep sedation.

Can I eat before a root canal?

Yes, you can usually eat up to an hour before a root canal. However, if you are undergoing sedation, you may need to stop eating earlier. Talk to your dentist to be sure.

Do root canals cause cancer?

No, there is no reliable evidence that root canals cause cancer.

Scientific methodologies from the 1950s drove this theory. The science on this is correlative, not causative. Root canal methods and materials have evolved many times over since those times and have been completely different since the 1970s.

That said, a poorly done root canal can and will have effects on the health of the rest of the body. Get a cone-beam CT (CBCT) every 3-5 years to check for root canal failure.

Will a root canal give me a blood infection (bacteremia)?

Bacteremia after a root canal happens in 15-20% of cases. This occurs when dental pathogens spread to the bloodstream. In a healthy individual, this lasts around 20 minutes and your body can easily fight off the bacteria.

For context, bacteremia is very common after dental cleanings — it’s generally not something to cause great concern.

In rare cases, patients can develop infective endocarditis, inflammation of the heart lining, as a result of bacteremia. Dentists used to — and still may — prescribe antibiotics as a prophylactic measure, but it’s unclear whether or not these are effective.

Why would my dentist not use a rubber dam for my root canal?

Rubber dams during root canal are controversial for patients with TMJ pain.

With a temporomandibular joint disorder (TMD), keeping your mouth open with a dental dam for up to 90 minutes during a root canal can cause significant discomfort. Some patients have TMJ pain for 6-8 weeks after the procedure.

In these cases, dentists may forego the use of a rubber dam or divide an appointment into multiple shorter sessions. Talk to your dentist about these options if you have TMD problems.

Can I get a root canal while I’m pregnant?

Available evidence suggests that root canal treatment is safe during pregnancy, particularly between weeks 13-21 of gestation. This treatment is associated with no significant increase in serious medical issues or adverse pregnancy outcomes.

The American Pregnancy Association emphasizes that, while root canals are considered safe while pregnant, it’s important to consider the risks of sedation, antibiotics, and x-rays that may be involved.

A single x-ray should not pose a risk to you or your baby. If possible, request a lower level of local anesthesia and skip other sedation. You should only take antibiotics if your dentist feels this is the only safe option, as antibiotics can affect fetal health.

References

- Sigurdsson, A. (2003). Pulpal diagnosis. Endodontic Topics, 5(1), 12-25. Abstract: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1601-1546.2003.00024.x

- Aaminabadi, N. A., Parto, M., Emamverdizadeh, P., Jamali, Z., & Shirazi, S. (2017). Pulp bleeding color is an indicator of clinical and histohematologic status of primary teeth. Clinical Oral Investigations, 21(5), 1831-1841. Abstract: https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s00784-017-2098-y

- Wong, A. W. Y., Tsang, C. S. C., Zhang, S., Li, K. Y., Zhang, C., & Chu, C. H. (2015). Treatment outcomes of single-visit versus multiple-visit non-surgical endodontic therapy: a randomised clinical trial. BMC oral health, 15(1), 1-11. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4684923/

- Aquilino, S. A., & Caplan, D. J. (2002). Relationship between crown placement and the survival of endodontically treated teeth. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, 87(3), 256-263. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11941351/

- Nagasiri, R., & Chitmongkolsuk, S. (2005). Long-term survival of endodontically treated molars without crown coverage: a retrospective cohort study. The Journal of prosthetic dentistry, 93(2), 164-170. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15674228/

- Kishen, A. (2006). Mechanisms and risk factors for fracture predilection in endodontically treated teeth. Endodontic topics, 13(1), 57-83. Abstract: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1601-1546.2006.00201.x

- Ventola, C. L. (2015). The antibiotic resistance crisis: part 1: causes and threats. Pharmacy and therapeutics, 40(4), 277. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4378521/

- Bansal, R., Jain, A., Goyal, M., Singh, T., Sood, H., & Malviya, H. S. (2019). Antibiotic abuse during endodontic treatment: A contributing factor to antibiotic resistance. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 8(11), 3518. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6881914/

- Aminoshariae, A., & Kulild, J. C. (2016). Evidence-based recommendations for antibiotic usage to treat endodontic infections and pain: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 147(3), 186-191. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26724957/

- Gould, K., & Hakan, B. European Society of Endodontology position statement: the use of antibiotics in endodontics. Full text: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1111/iej.12781

- Erazo, D., & Whetstone, D. R. (2019). Dental Infections. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542165/

- Polycarpou, N., Ng, Y. L., Canavan, D., Moles, D. R., & Gulabivala, K. (2005). Prevalence of persistent pain after endodontic treatment and factors affecting its occurrence in cases with complete radiographic healing. International endodontic journal, 38(3), 169-178. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15743420/

- Vieira, A. R., Siqueira Jr, J. F., Ricucci, D., & Lopes, W. S. (2012). Dentinal tubule infection as the cause of recurrent disease and late endodontic treatment failure: a case report. Journal of endodontics, 38(2), 250-254. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22244647/

- Simon, S., Machtou, P., Tomson, P., Adams, N., & Lumley, P. (2008). Influence of fractured instruments on the success rate of endodontic treatment. Dental update, 35(3), 172-179. Full text: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Phillip_Tomson/publication/5344158_Influence_of_Fractured_Instruments_on_the_Success_Rate_of_Endodontic_Treatment/links/0912f50eae53de6861000000/Influence-of-Fractured-Instruments-on-the-Success-Rate-of-Endodontic-Treatment.pdf

- Cheung, G. S. (2007). Instrument fracture: mechanisms, removal of fragments, and clinical outcomes. Endodontic Topics, 16(1), 1-26. Abstract: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/j.1601-1546.2009.00239.x

- Lin, L. M., Rosenberg, P. A., & Lin, J. (2005). Do procedural errors cause endodontic treatment failure?. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 136(2), 187-193. Abstract: https://jada.ada.org/article/S0002-8177(14)64408-1/abstract

- Bernstein, S. D., Matthews, A. G., Curro, F. A., Thompson, V. P., Craig, R. G., Horowitz, A. J., … & Collie, D. (2012). Outcomes of endodontic therapy in general practice: a study by the Practitioners Engaged in Applied Research and Learning Network. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 143(5), 478-487. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4394182/

- Burry, J. C., Stover, S., Eichmiller, F., & Bhagavatula, P. (2016). Outcomes of primary endodontic therapy provided by endodontic specialists compared with other providers. Journal of Endodontics, 42(5), 702-705. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27004720/

- Sigurdsson, A., Garland, R. W., Le, K. T., & Woo, S. M. (2016). 12-month healing rates after endodontic therapy using the novel GentleWave system: a prospective multicenter clinical study. Journal of endodontics, 42(7), 1040-1048. Abstract: https://nyuscholars.nyu.edu/en/publications/12-month-healing-rates-after-endodontic-therapy-using-the-novel-g

- Touré, B., Faye, B., Kane, A. W., Lo, C. M., Niang, B., & Boucher, Y. (2011). Analysis of reasons for extraction of endodontically treated teeth: a prospective study. Journal of endodontics, 37(11), 1512-1515. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22000453/

- Iqbal, M. K., & Kim, S. (2008). A review of factors influencing treatment planning decisions of single-tooth implants versus preserving natural teeth with nonsurgical endodontic therapy. Journal of endodontics, 34(5), 519-529. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18436028/

- Banchs, F., & Trope, M. (2004). Revascularization of immature permanent teeth with apical periodontitis: new treatment protocol?. Journal of endodontics, 30(4), 196-200. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15085044/

- Nakashima, M., Iohara, K., Murakami, M., Nakamura, H., Sato, Y., Ariji, Y., & Matsushita, K. (2017). Pulp regeneration by transplantation of dental pulp stem cells in pulpitis: a pilot clinical study. Stem cell research & therapy, 8(1), 61. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5345141/

- Kim, S. G., Malek, M., Sigurdsson, A., Lin, L. M., & Kahler, B. (2018). Regenerative endodontics: a comprehensive review. International endodontic journal, 51(12), 1367-1388. Full text: https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/iej.12954

- Lin, L. M., & Kahler, B. (2017). A review of regenerative endodontics: current protocols and future directions. Journal of Istanbul University Faculty of Dentistry, 51(3 Suppl 1), S41. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5750827/

- Rahimi, S., Janani, M., Lotfi, M., Shahi, S., Aghbali, A., Pakdel, M. V., … & Ghasemi, N. (2014). A review of antibacterial agents in endodontic treatment. Iranian endodontic journal, 9(3), 161. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4099945/

- Domb, W. C. (2014). Ozone therapy in dentistry: a brief review for physicians. Interventional Neuroradiology, 20(5), 632-636. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4243235/

- Ajeti, N. N., Pustina-Krasniqi, T., & Apostolska, S. (2018). The effect of gaseous ozone in infected root canal. Open access Macedonian journal of medical sciences, 6(2), 389. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5839455/

- Chiniforush, N., Pourhajibagher, M., Shahabi, S., Kosarieh, E., & Bahador, A. (2016). Can antimicrobial photodynamic therapy (aPDT) enhance the endodontic treatment?. Journal of lasers in medical sciences, 7(2), 76. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4909016/

- Debelian, G. J., Olsen, I., & Tronstad, L. (1995). Bacteremia in conjunction with endodontic therapy. Dental Traumatology, 11(3), 142-149. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/7641631/

- Brincat, M., Savarrio, L., & Saunders, W. (2006). Endodontics and infective endocarditis–is antimicrobial chemoprophylaxis required?. International Endodontic Journal, 39(9), 671-682. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/16916356/

- Sahebi, S., Moazami, F., Afsa, M., & Zade, M. R. N. (2010). Effect of lengthy root canal therapy sessions on temporomandibular joint and masticatory muscles. Journal of dental research, dental clinics, dental prospects, 4(3), 95. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3429977/

- Michalowicz, B. S., DiAngelis, A. J., Novak, M. J., Buchanan, W., Papapanou, P. N., Mitchell, D. A., … & Matseoane, S. (2008). Examining the safety of dental treatment in pregnant women. The Journal of the American Dental Association, 139(6), 685-695. Abstract: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18519992/

Why You Should Protect Your Teeth With a Mouthguard During Exercise

Why You Should Protect Your Teeth With a Mouthguard During Exercise