Table of Contents[Hide][Show]

Headlines plaster the importance of gut health on every major health-related website. The gut is central to human health, and at its core, gut health is determined by the diversity and population of the gut microbiome (also known as gut microbiota or gut flora).

In 2000, the US Surgeon General called the mouth “the mirror of health and disease in the body.” It’s not a closed system.

If gut health is so key to our understanding of health and disease, and the mouth mirrors the health of the body, it should come as no surprise that oral health is intrinsically linked with gut health.

This is where our understanding of the oral microbiome begins.

What is the oral microbiome?

Like the other three microbiomes of the body (gut, skin, and vaginal), the oral microbiome is a collection of bacteria that affects the progression of health and disease.

The mouth has a variety of micro-environments that host different bacterial populations: the tongue, the hard palate, the teeth, the area around the tooth surfaces, above the gums, and below the gums.

It’s the first meeting place between the alimentary canal (the entire passage along which food passes through the body), the immune system, and the outside world.

Several hundred species of bacteria (700+ identified at the time of this writing) exist within this delicately balanced colony. The most prevalent of these are also found in the other three biomes in smaller numbers. This balance of bacteria in the oral cavity is the second most diverse biome of the body, second only to the gut.

An imbalance in the oral microbiome, like an imbalance in the gut, will lead to inflammation, illness, and disease.

Many of these will occur in the mouth (tooth decay, gingivitis, oral thrush, etc.) but they also have a major impact on gut and overall health.

A major 2019 study in the Journal of Oral Microbiology discovered that bacterial populations from the mouth make their way to the gut microbiota. This can alter immune responses and potentially lead to systemic diseases.

In particular, this study names the P. gingivalis bacteria as one that is found in both a dysbiotic gut microbiome and oral cavities of those with chronic gum disease (periodontitis).

The oral microbiome is a major player in the mouth-body connection. Sadly, many approaches to dental care don’t consider how important it is to support a healthy flora within the mouth. Instead, we’re told to disinfect, sanitize, and “clean” the mouth.

Let’s take a look at how this biome can impact your gut and overall health.

Get Dr. B’s Dental Health Tips

Free weekly dental health advice in your inbox, plus 10 Insider Secrets to Dental Care as a free download when you sign up

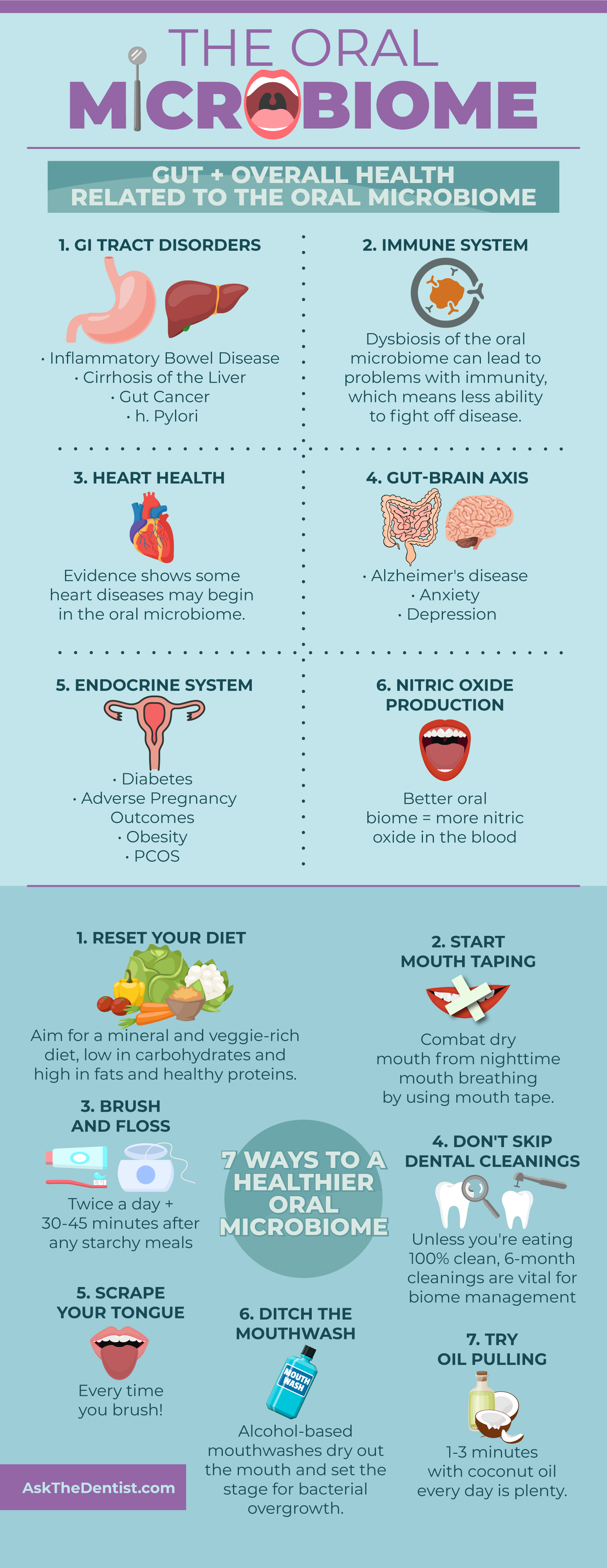

How Oral Biome Diversity Impacts Gut & Overall Health

As a dentist, I was taught all about how the bacteria in the mouth cause oral disease. From gingivitis to candida/oral thrush to cavities, an overabundance of pathogenic (disease-causing) bacteria can cause a slew of problems.

What I wasn’t made aware of—what even the scientific community didn’t realize at the time—is that this same imbalance affects the health of the rest of your body.

In talking with Cass Nelson-Dooley, MS, an ethnopharmacologist who has studied the oral microbiome at length, I found that some of these issues may arise from a similar issue to what we know as “leaky gut.” Cass refers to the oral equivalent of this as gingival epithelium permeability, although she’s also jokingly called it “leaky mouth” for several years, striking an obvious connection to gut health.

Like leaky gut, this permeability in the mouth is closely connected to the ability of bacteria to make their way past the gums into the rest of the body. It’s been most studied in conjunction with diabetes, a disease known to run in tandem with chronic periodontitis.

Cass’ research led her to the conclusion that 45% of the bacteria in the mouth are also found in the gut. From her recent book on the oral microbiome:

“Every time you swallow, you are seeding your gastrointestinal tract with bacteria, fungi, and viruses from your mouth—140 billion per day, to be exact.”

This is one reason that the incredibly high prevalence of oral diseases like cavities or gum disease is sometimes considered a “mismatch disease,” much like diabetes. It’s called this because these diseases weren’t common (or even in existence) in historical times before the modern diet emerged.

Some experts claim that our bodies’ evolutionary standard is “mismatched” to modern diets, leading to high rates of diseases that are affected heavily by the modern, carbohydrate-heavy diet.

I’ll get to dietary ways to support the oral biome below, but first: Oral infection can cause major issues within the rest of the body in a variety of ways. These include bacteremia (escape of bacteria through the gums to the bloodstream), system-wide inflammation, and infection of bacterial toxins that make their way throughout the body.

Two of the major bacterial groups in the oral biome that can impact the rest of health most notably include Prevotella and Veillonella.

Beginning with the gut, here are the major systems and functions of the body that are impacted by the health of your oral microbiome.

1. Gastrointestinal Tract

While gut dysbiosis (an imbalance of the microbiome) doesn’t only lead to GI tract problems, that’s one place dysbiosis can begin wreaking havoc.

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) include multiple diseases, most commonly understood as inflammatory bowel syndrome (IBS), Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis.

These diseases all have one huge factor in common: chronic, persistent inflammation.

There are many interactions that may lead to IBD, like genetics and epigenetics, immune responses, and bacterial imbalances. However, one such factor that’s gained more attention in recent years is the connection between IBD and oral disease.

Patients with IBD frequently struggle with oral and dental symptoms like dry mouth, mouth ulcers, and a rare inflammation of the lips and mouth called pyostomatitis vegetans.

While the research is somewhat limited on the oral microbiome quality and diversity in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases, here’s what we know:

- Those with IBD have higher amounts of these dominant pathogenic oral bacterial species: Streptococcus, Prevotella, Neisseria, Haemophilus, Veillonella, and Gemella.

- Inflammatory responses in IBD are associated with dysbiosis of the oral microbiome.

- Some strains of Klebsiella bacteria in the mouth instigate the production of inflammatory TH1 cells when they colonize within the gut. These antibiotic-resistant bacterial strains tend to colonize only in a gut that is already dysbiotic. Klebsiella can “elicit a severe gut inflammation in the context of a genetically susceptible host.”

Cirrhosis of the Liver

Liver diseases, over time, often lead to cirrhosis, a scarring of the liver. Those with liver cirrhosis have a specifically dysbiotic gut microbiome.

Of the problematic bacterial species in liver cirrhosis, 54% originate in the mouth.

The biomarkers used to recognize these imbalances are very similar to those in patients with both diabetes and IBD.

Gut-Related Cancers

Both advanced gum disease and tooth loss, which are caused by oral pathogens, increase the risk of gastrointestinal, pancreatic, and liver cancer.

This seems to happen for two reasons. One, oral bacteria can cause systemic inflammation when they make their way to the bloodstream and/or digestive system. Second, there is some evidence that they may activate carcinogens present in the mouth after smoking or drinking alcohol.

In the case of pancreatic cancer, researchers have discovered that P. gingivalis and A. actinomycetemcomitans drive risk higher, while Leptotrichia bacteria in the mouth actually decrease your risk of this type of cancer. This begins to reveal how the oral microbiome plays a part in not only disease progression, but prevention and health as well.

H. pylori

The Helicobacter pylori bacteria can infect the stomach and cause peptic (stomach) ulcers. H. pylori infection is incredibly common, as this bacteria is present in over half the world’s population.

However, it’s not just the stomach where this bacteria can live. Even after wiping out H. pylori with antibiotics, it’s common to get re-infected. How? H. pylori is incredibly common within the mouth, particularly in people who have been diagnosed with H. pylori infection within the gut.

If you struggle with recurrent H. pylori infection, it’s possible your mouth can be the source. Whether the bacteria is making its way to the gut via teeth cleanings and bacteremia, or via “leaky mouth,” it’s important to address the infection from all sides to truly get rid of it.

2. Immune System

As 70%+ of your immune system is located in your gut, it’s no shock that the gut microbiome plays a big part in immunity. However, immunity actually begins in the mouth, the headwater to the entire digestive system.

In ancient oral microbiomes, many of the same bacteria as we see today could cause systemic disease. In particular, those with a buildup of dental calculus (plaque) had poorer immune responses to not only oral, but system-wide diseases.

Proper immune response is one way your body keeps a handle on normal inflammatory processes. Pathogens in the oral cavity can overthrow this delicate balance and create chronic inflammation.

Beyond just the immune responses you need for fighting a cold or flu, these disruptions in immunity can lead to heart disease (which I cover below) and autoimmune conditions.

Specifically, oral microbiome dysbiosis is implicated in rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune condition. Interestingly, this study discovered that some of this dysbiosis can be reversed with good dental hygiene.

Instances of HIV/AIDS may also be affected by oral microbiome health. There is evidence that biome diversity in the mouth is much different in unmanaged HIV/AIDS than in healthy controls.

3. Cardiovascular Health

Related to both the gut and immune function, atherosclerosis may also find its roots in oral microbiome problems. This buildup of plaque within the arteries can limit oxygen throughout the body as well as nutrients in the bloodstream.

Risk of cardiovascular disease and oral infections, namely, periodontitis, are closely correlated. These are both very tightly related to inflammation, both in the mouth and throughout the entire body.

4. Gut-Brain Axis

The gut-brain axis is a well-established part of scientific theory. From depression to Alzheimer’s, a healthy gut biome is integral to decreasing your risk for diseases of the brain and nervous system.

Because the oral microbiome is an extension of this axis, oral health may affect brain health through its influence on the gut.

A few examples of this include Alzheimer’s disease, anxiety, and depression.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Recently, gingival bacteria has earned the public eye as a potential cause of Alzheimer’s disease. A groundbreaking study released in early 2019 proposed a rare causative link (not just a correlation) between the bacteria most responsible for gum disease and Alzheimer’s disease in the brain. For years, researchers have understood there was a connection between these two conditions, but not much about how or why this was the case.

Furthermore, researchers were able to develop a gingipain inhibitor that, in animal subjects, not only reduced the risk for the disease but actually reversed the brain infection and rescued neurons in the hippocampus.

The theory behind this connection is that P. gingivalis bacteria can make its way to the spinal cord and then the brain. Once it reaches the brain, it creates compounds called gingipains that correlate directly with the amount of toxic tau tangles found in the brains of those with Alzheimer’s.

Anxiety & Depression

A major factor of the gut-brain axis is the way it influences anxiety and depression. This is thought to begin as early as birth, when the vaginal microbiota is transferred to a new baby during delivery.

Effective depression or anxiety treatment must always include resolution of a dysbiotic gut. Sadly, attention to the oral microbiome is often ignored in this process. However, there is a direct correlation between poor dental health, tooth pain, bleeding gums, and anxiety/depression.

5. Endocrine System

Diseases of the endocrine system may be influenced, in part, by the oral microbiome.

Diabetes

As I mentioned earlier, diabetes is one of the “mismatch diseases” in modern life. It’s tightly related to poor diet and lifestyle factors, like being sedentary or exposed to household toxins.

However, the risk of diabetes goes up astronomically after the development of periodontitis, which is itself an inflammatory condition directly caused by a dysbiotic oral microbiome.

People with diabetes have drastically different oral biomes than non-diabetics. Researchers have yet to determine which happens first (dysbiosis of the gut and oral microbiomes or the development of diabetes), but it seems to be a two-way street.

Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes

Adverse pregnancy outcomes (APOs) include problems with pregnancy in birth, including:

- Preterm labor

- Preterm membrane rupture

- Preeclampsia

- Miscarriage

- Intrauterine growth retardation (a major growth issue connected to fetal morbidity and some congenital anomalies)

- Low birth weight

- Stillbirth

- Neonatal sepsis

The oral bacteria most often implicated in these APOs is F. nucleatum. It has been found in placental and fetal tissues after many of the conditions above. This happens when the bacteria is transferred from the mother, through periodontal disease, to the placenta and the fetus. Inflammation and dysfunctional immune responses result in potential tissue damage and improper fetal development.

P. gingivalis and Bergeyella bacteria may also lead to some of these adverse pregnancy outcomes. Researchers hope that, by identifying these common pathogens, earlier and more accurate diagnosis will help screen for those at risk.

Obesity

The causes of obesity are incredibly broad, but one 2009 study may suggest a cause that begins in the oral microbiome. In over 98% of the women with obesity studied, the bacteria Selenomonas noxia was found in very high levels in saliva compared to the control group.

From this study, we can’t determine a cause-and-effect. For instance, the dietary patterns in many obese people dysregulate the oral microbiome because they’re so high in starchy carbohydrates and sugar.

That being said, the fact that so many of the subjects had one particular pathogen in common deserves further interest.

Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome (PCOS)

PCOS, an endocrine disorder that affects up to 21 percent of women of childbearing age, is considered to be the most common cause of infertility in the developed world.

This condition is intrinsically linked to the quality of the gut microbiome. A high prevalence of Prevotella bacteria, in particular, is implicated in polycystic ovarian syndrome.

Recognize that bacteria? You should—it’s one of the common pathogenic oral bacteria that’s also found in the gut.

In a 2016 study, the saliva of women with PCOS tested for an overabundance of Prevotella, coming in at higher levels than any other bacteria.

6. Nitric Oxide Production

In the mouth and body, nitric oxide is a vital nutrient to support the body’s natural repair processes. It’s involved in systems from the gut to the brain and can improve blood pressure, digestion, cancer risk, chronic inflammation, sleep, endurance, and insulin resistance.

When the oral microbiome contains a high number of “nitrate-reducing bacteria,” nitric oxide production decreases. This can lead to a cascade of problems throughout the body, including (but not limited to) higher risk of high blood pressure and other heart diseases.

High-Sugar Diets: Bad for the Gut & Mouth

When it comes to a diet to support the gut and oral microbiomes, the results are clear: getting rid of our sugar addiction is key.

A diet high in sugar and other starchy carbohydrates is bad for bacterial health in three ways:

- It leads to increased inflammation, which has far-reaching effects on the entire body (often beginning with the mouth and gut).

- In the mouth, frequent sugar intake moves the pH in the mouth to be more acidic. An acidic environment contributes to the demineralization of teeth.

- Plaque buildup from carbohydrate-rich diets contribute to dysbiosis in the oral microbiome, contributing to problems from cavities to heart disease.

Poor oral hygiene, high sugar intake, and low salivary flow all change the pH in the mouth. This selects for certain bacteria that like acidic conditions and make acid, which further lowers the pH and can contribute to tooth decay. However, diet is typically the most important on this list, although oral hygiene habits are usually more discussed.

All in all, it sets up an acidic environment of lower bacterial diversity, where non-pathogenic Streptococcus die out and S.mutans can thrive.

In a more acidic environment, S. mutans and yeast take over, eventually causing dental caries. While the literature doesn’t use the term “dysbiosis” in regards to oral health, the microbial imbalance in the mouth that triggers the development of dental caries certainly qualifies as dysbiosis.

Paleo people didn’t need dental cleanings or probiotic supplements, but modern man does. This all roots back to the fact that a Paleo-centric diet is high in vegetables, non-farmed animal proteins, healthy fats, limited carbohydrates, and fruits.

Candidiasis of the mouth (oral thrush) is another sugar-related symptom of a systemic issue with sugar. In the gut as well as the oral cavity, Candida overgrowth is best treated with a multi-system approach that always includes cutting out sugar, and includes other treatments like glutamine rinse, chewable CoQ10, and vitamins and minerals to promote immune function.

Pregnancy, Birth, and the Microbiota

One of the first set of questions I ask new patients (that often gets me a raised eyebrow) has to do with their birth and infancy. I want to know:

- If they were delivered vaginally or via C-section, and

- If they were breastfed as an infant

These questions matter because your microbiome’s diversity (all four of them!) begin with pre-conception and continue for your entire life. The health of bacterial ratios within the body begins transferring to a developing fetus during early pregnancy.

During vaginal delivery, the microbiomes are transferred to the infant. A 2011 study shows that this specifically impacts the diversity of the oral microbiome as well as the 2-3 others (depending on gender).

While C-section is necessary in some cases and can be a great thing for risky deliveries, missing out on the biome is a big deal. It’s known to contribute to the risk for gut and overall health issues including celiac disease, asthma, type 1 diabetes, and obesity. In fact, Slackia exigua, one oral pathogen, is found exclusively in C-section delivered babies.

That’s why vaginal microbial transfer, a newer method of restoring microbiota to Caesarean-born infants, has been proposed as a helpful solution.

Breastfeeding also plays into the development of the oral microbiome. During breastfeeding, the mother’s microbiota is again supporting the development of the infant’s oral and gut microbiomes.

While not every mom is able (or even chooses) to breastfeed, the answers to these questions help give me a baseline for what to expect from my patient’s oral biome. This, in turn, can help me advise them on how to support their oral microbiome and improve their dental and overall health.

7 Ways to Support Your Oral Microbiome

Beyond your birth and breastfeeding history, there are several ways to support the health of your oral microbiome. By extension, this can help make your entire body healthier!

1. Reset Your Diet

There are many foods that support oral health by controlling the biofilm on your teeth and reducing plaque buildup. These can become complex dietary changes, so here are the basic “dos” and “don’ts”:

Do…

- Eat mineral-rich foods like grass-fed dairy, high-quality seafood, and leafy greens.

- Get plenty of healthy fats, like grass-fed butter or ghee, fatty fish, nuts, healthy oils (coconut, avocado, and olive oils are a great place to start), and fatty cuts of grass-fed meats.

- Get as many non-starchy veggies in your diet as possible.

- Eat vitamin-K rich foods, like chicken liver, pastured eggs, and grass-fed butter.

- Drink a ton of water to keep your mouth and body well-hydrated.

- Consider chewing sugar-free gum to help remineralize your teeth with xylitol (just be careful, as it’s toxic to cats and dogs).

Don’t…

- Fill more than 15% of your plate with carbohydrates. The worst of these for your bacterial diversity include white bread, pasta, rice, crackers, and the like. Complex carbohydrates aren’t much better for your teeth than the refined versions, but they’re manageable in moderation.

- Eat sugary candy, cookies, or desserts every day. These treats offer very little nutrition in exchange for excessive calories and, most concerning, sugar compounds that can upset your biome in as little as 1 day.

- Drink soda, fruit juices, coffee, kombucha, or alcohol over long periods of time. While coffee and kombucha offer some health benefits, sipping on these throughout the day contributes to demineralization. If you’re going for one of these beverages, try keeping it to 20-30 minutes, then brushing about 30-45 minutes afterwards.

- Overdo it with phytic acid. Wheat products, rice, and beans/legumes are high in phytic acid, which can contribute to oral microbiome issues.

2. Start Mouth Taping

I’ve mentioned it once already, but a dry mouth is a perfect home for bacterial overgrowth. In fact, I think it might be a bigger contributor to cavities, gum disease, and bad breath than even diet!

By mouth taping at night to prevent breathing through your mouth, you can drastically cut down on dry mouth issues. In turn, this will keep your biome in good shape and drive down your risk for oral, gut, and overall disease.

3. Brush and Floss Regularly

Particularly for those still on a standard Western diet, brushing and flossing are key to biofilm and oral microbiome management.

I recommend brushing and flossing right after waking up, immediately before bed, and 30-45 minutes after a carbohydrate-rich meal.

4. Don’t Skip Your Cleanings

In an ideal world, if a patient were eating 100% Paleo or keto, s/he could probably go 12-18 months between cleanings. However, very few people (my own family included!) have the desire or ability to stick to a strict diet that closely.

That’s why 6-month teeth cleanings are important to keeping your oral microbiome healthy. The plaque buildup your hygienist removes can otherwise contribute to the dysbiotic growth of pathogenic oral bacteria.

5. Scrape Your Tongue

The tongue is sometimes forgotten in the course of dental hygiene habits. However, there’s a simple solution: start tongue scraping.

Scraping your tongue is an easy, inexpensive, and quick habit to develop that can remove the buildup of bacteria on the tongue. It can even make your food taste better and improve bad breath!

6. Ditch the Conventional Mouthwash

After learning so much about the importance of a good bacterial diversity in the mouth, it followed pretty clearly to me that killing “up to 99.9% of oral germs” isn’t a good thing.

Using conventional mouthwashes is to the oral microbiome what antibiotics are to the gut microbiome. On rare occasions, they can knock out a particularly bad case of the overgrowth of one or two bacterial strains and give you a “clean slate.”

However, when used more than occasionally, alcohol-based mouthwash dries out the mouth in addition to eliminating your mouth’s built-in immunities to oral disease.

Instead, try a DIY mouthwash or a natural brand meant to support the microbiota of the mouth.

7. Try Oil Pulling

Unlike mouthwash, oil pulling is a great habit that promotes microbial diversity in the mouth while decreasing inflammation, especially if you use coconut oil.

20 minutes a day isn’t necessary—I recommend oil pulling just 1-3 minutes every morning. Just remember to spit the oil into the trash, not the sink, as it can clog pipes as it re-hardens.

Key Takeaways: The Oral Microbiome

As we can see, the oral microbiome is closely related both to the health of the gut but also the entire body by extension.

By supporting a healthy microbiome, rather than eliminating bacterial diversity with conventional antiseptic treatments (like mouthwash), you can support oral and overall health.

What Exactly Is the Mouth-Body Connection?Further Reading

Heal Your Oral Microbiome by Cass Nelson-Dooley, M.S.

References

- Shreiner, A. B., Kao, J. Y., & Young, V. B. (2015). The gut microbiome in health and in disease. Current opinion in gastroenterology, 31(1), 69. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4290017/

- Dewhirst, F. E., Chen, T., Izard, J., Paster, B. J., Tanner, A. C., Yu, W. H., … & Wade, W. G. (2010). The human oral microbiome. Journal of bacteriology, 192(19), 5002-5017. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2944498/

- Deo, P. N., & Deshmukh, R. (2019). Oral microbiome: Unveiling the fundamentals. Journal of oral and maxillofacial pathology: JOMFP, 23(1), 122. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6503789/

- Olsen, I., & Yamazaki, K. (2019). Can oral bacteria affect the microbiome of the gut?. Journal of oral microbiology, 11(1), 1586422. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6427756/

- Gao, L., Xu, T., Huang, G., Jiang, S., Gu, Y., & Chen, F. (2018). Oral microbiomes: more and more importance in oral cavity and whole body. Protein & cell, 9(5), 488-500. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5960472/

- LOE, H. (1993). Periodontal Disease. DIABETES CARE, 16, 329. Citation: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8422804

- Nelson-Dooley, C., & Olmstead, S. F. (2015). The microbiome and overall health part 5: the oropharyngeal microbiota’s far-reaching role in immunity, gut health, and cardiovascular disease. Complementary Prescriptions. ProThera, Inc. Practitioner Newsletter. Reno, NV: ProThera, Inc, 1(4), 4. Full text: https://www.drkarafitzgerald.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/2015-Oral-Microbiome-Nelson-Dooley-Olmstead.pdf

- Han, Y. W., & Wang, X. (2013). Mobile microbiome: oral bacteria in extra-oral infections and inflammation. Journal of dental research, 92(6), 485-491. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3654760/

- Yamashita, Y., & Takeshita, T. (2017). The oral microbiome and human health. Journal of oral science, 59(2), 201-206. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/28637979

- Pickard, J. M., Zeng, M. Y., Caruso, R., & Núñez, G. (2017). Gut microbiota: role in pathogen colonization, immune responses, and inflammatory disease. Immunological reviews, 279(1), 70-89. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5657496/

- Caballero, S., & Pamer, E. G. (2015). Microbiota-mediated inflammation and antimicrobial defense in the intestine. Annual review of immunology, 33, 227-256. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4540477/

- Atarbashi-Moghadam, S., Lotfi, A., & Atarbashi-Moghadam, F. (2016). Pyostomatitis vegetans: a clue for diagnosis of silent Crohn’s disease. Journal of clinical and diagnostic research: JCDR, 10(12), ZD12. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5296587/

- Said, H. S., Suda, W., Nakagome, S., Chinen, H., Oshima, K., Kim, S., … & Mano, S. (2013). Dysbiosis of salivary microbiota in inflammatory bowel disease and its association with oral immunological biomarkers. DNA research, 21(1), 15-25. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3925391/

- Atarashi, K., Suda, W., Luo, C., Kawaguchi, T., Motoo, I., Narushima, S., … & Thaiss, C. A. (2017). Ectopic colonization of oral bacteria in the intestine drives TH1 cell induction and inflammation. Science, 358(6361), 359-365. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5682622/

- Qin, N., Yang, F., Li, A., Prifti, E., Chen, Y., Shao, L., … & Zhou, J. (2014). Alterations of the human gut microbiome in liver cirrhosis. Nature, 513(7516), 59. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25079328/

- Meurman, J. H. (2010). Oral microbiota and cancer. Journal of oral microbiology, 2(1), 5195. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3084564/

- Rogers, A. B., & Fox, J. G. (2004). Inflammation and Cancer I. Rodent models of infectious gastrointestinal and liver cancer. American Journal of Physiology-Gastrointestinal and Liver Physiology, 286(3), G361-G366. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/14766534/

- Ahn, J., Chen, C. Y., & Hayes, R. B. (2012). Oral microbiome and oral and gastrointestinal cancer risk. Cancer Causes & Control, 23(3), 399-404. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3767140/

- Fan, X., Alekseyenko, A. V., Wu, J., Peters, B. A., Jacobs, E. J., Gapstur, S. M., … & Ravel, J. (2018). Human oral microbiome and prospective risk for pancreatic cancer: a population-based nested case-control study. Gut, 67(1), 120-127. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5607064/

- Zou, Q. H., & Li, R. Q. (2011). Helicobacter pylori in the oral cavity and gastric mucosa: a meta‐analysis. Journal of Oral Pathology & Medicine, 40(4), 317-324. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21294774

- Vighi, G., Marcucci, F., Sensi, L., Di Cara, G., & Frati, F. (2008). Allergy and the gastrointestinal system. Clinical & Experimental Immunology, 153, 3-6. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2515351/

- Round, J. L., & Mazmanian, S. K. (2009). The gut microbiota shapes intestinal immune responses during health and disease. Nature reviews immunology, 9(5), 313. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4095778/

- Warinner, C., Rodrigues, J. F. M., Vyas, R., Trachsel, C., Shved, N., Grossmann, J., … & Speller, C. (2014). Pathogens and host immunity in the ancient human oral cavity. Nature genetics, 46(4), 336. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3969750/

- Zhang, X., Zhang, D., Jia, H., Feng, Q., Wang, D., Liang, D., … & Lan, Z. (2015). The oral and gut microbiomes are perturbed in rheumatoid arthritis and partly normalized after treatment. Nature medicine, 21(8), 895. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26214836/

- Heron, S. E., & Elahi, S. (2017). HIV infection and compromised mucosal immunity: oral manifestations and systemic inflammation. Frontiers in immunology, 8, 241. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5339276/

- Slocum, C., Kramer, C., & Genco, C. A. (2016). Immune dysregulation mediated by the oral microbiome: potential link to chronic inflammation and atherosclerosis. Journal of internal medicine, 280(1), 114-128. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26791914

- El Kholy, K., Genco, R. J., & Van Dyke, T. E. (2015). Oral infections and cardiovascular disease. Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism, 26(6), 315-321. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25892452

- Carabotti, M., Scirocco, A., Maselli, M. A., & Severi, C. (2015). The gut-brain axis: interactions between enteric microbiota, central and enteric nervous systems. Annals of gastroenterology: quarterly publication of the Hellenic Society of Gastroenterology, 28(2), 203. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4367209/

- Foster, J. A., & Neufeld, K. A. M. (2013). Gut–brain axis: how the microbiome influences anxiety and depression. Trends in neurosciences, 36(5), 305-312. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23384445

- Okoro, C. A., Strine, T. W., Eke, P. I., Dhingra, S. S., & Balluz, L. S. (2012). The association between depression and anxiety and use of oral health services and tooth loss. Community dentistry and oral epidemiology, 40(2), 134-144. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21883356

- Emrich, L. J., Shlossman, M., & Genco, R. J. (1991). Periodontal disease in non‐insulin‐dependent diabetes mellitus. Journal of periodontology, 62(2), 123-131. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2027060/

- Casarin, R. C. V., Barbagallo, A., Meulman, T., Santos, V. R., Sallum, E. A., Nociti, F. H., … & Gonçalves, R. B. (2013). Subgingival biodiversity in subjects with uncontrolled type‐2 diabetes and chronic periodontitis. Journal of periodontal research, 48(1), 30-36. Abstract: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22762355/

- Vandenbosche, R. C., & Kirchner, J. T. (1998). Intrauterine growth retardation. American family physician, 58(6), 1384-90. Full text: https://www.aafp.org/afp/1998/1015/p1384.html

- Han, Y. W., Shen, T., Chung, P., Buhimschi, I. A., & Buhimschi, C. S. (2009). Uncultivated bacteria as etiologic agents of intra-amniotic inflammation leading to preterm birth. Journal of clinical microbiology, 47(1), 38-47. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2620857/

- Goodson, J. M., Groppo, D., Halem, S., & Carpino, E. (2009). Is obesity an oral bacterial disease?. Journal of dental research, 88(6), 519-523. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2744897/

- Joham, A. E., Teede, H. J., Ranasinha, S., Zoungas, S., & Boyle, J. (2015). Prevalence of infertility and use of fertility treatment in women with polycystic ovary syndrome: data from a large community-based cohort study. Journal of women’s health, 24(4), 299-307. Abstract: https://www.liebertpub.com/doi/abs/10.1089/jwh.2014.5000

- Guo, Y., Qi, Y., Yang, X., Zhao, L., Wen, S., Liu, Y., & Tang, L. (2016). Association between polycystic ovary syndrome and gut microbiota. PLoS One, 11(4), e0153196. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4836746/

- Hyde, E. R., Andrade, F., Vaksman, Z., Parthasarathy, K., Jiang, H., Parthasarathy, D. K., … & Bryan, N. S. (2014). Metagenomic analysis of nitrate-reducing bacteria in the oral cavity: implications for nitric oxide homeostasis. PLoS One, 9(3), e88645. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3966736/

- Kruis, W., Forstmaier, G., Scheurlen, C., & Stellaard, F. (1991). Effect of diets low and high in refined sugars on gut transit, bile acid metabolism, and bacterial fermentation. Gut, 32(4), 367-371. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1379072/

- Martins, N., Ferreira, I. C., Barros, L., Silva, S., & Henriques, M. (2014). Candidiasis: predisposing factors, prevention, diagnosis and alternative treatment. Mycopathologia, 177(5-6), 223-240. Full text: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Natalia_Martins10/publication/262024979_Candidiasis_Predisposing_Factors_Prevention_Diagnosis_and_Alternative_Treatment/links/0deec536ab042181f5000000/Candidiasis-Predisposing-Factors-Prevention-Diagnosis-and-Alternative-Treatment.pdf

- Lif Holgerson, P., Harnevik, L., Hernell, O., Tanner, A. C. R., & Johansson, I. (2011). Mode of birth delivery affects oral microbiota in infants. Journal of dental research, 90(10), 1183-1188. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3173012/

- Dominguez-Bello, M. G., De Jesus-Laboy, K. M., Shen, N., Cox, L. M., Amir, A., Gonzalez, A., … & Mendez, K. (2016). Partial restoration of the microbiota of cesarean-born infants via vaginal microbial transfer. Nature medicine, 22(3), 250. Full text: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5062956/

- Kilian, M., Chapple, I. L. C., Hannig, M., Marsh, P. D., Meuric, V., Pedersen, A. M. L., … & Zaura, E. (2016). The oral microbiome–an update for oral healthcare professionals. British Dental Journal, 221(10), 657. Full text: https://www.nature.com/articles/sj.bdj.2016.865#ref11

3 Things to Do to Prevent Candida in the Mouth

3 Things to Do to Prevent Candida in the Mouth